FIRST STOP: TRAUMA DEPARTMENT

Most patients arrive by helicopter. It's not uncommon for a half-dozen critically wounded people to arrive at once. The flow of casualties is unrelenting.

Most patients arrive by helicopter. It's not uncommon for a half-dozen critically wounded people to arrive at once. The flow of casualties is unrelenting.

Army Cpl. Eddie Ward, 19, lost most of his right leg in a land mine explosion. A surgical team at the NATO hospital at Kandahar Airfield prepares to clean his wounds. At left is Lt. Cmdr. Kirk Sundby; at right is Lt. Col Rob Stiegelmar. Both are Canadian orthopedic surgeons.

Navy Lt. Joelle Annandono, far left, helps clean the wounds of Cpl. Eddie Ward. The operation took nearly three hours. "This is one of the dirtiest wounds I've seen," Annandono said.

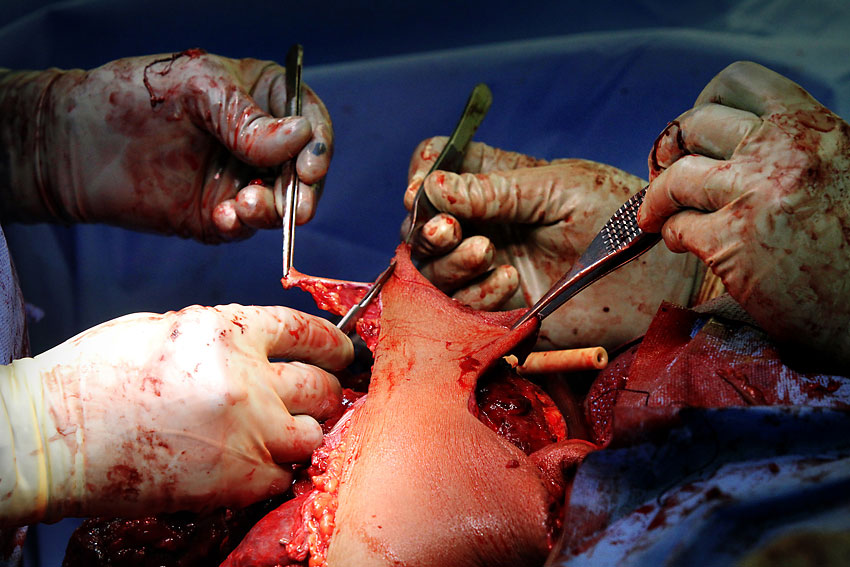

Surgeons work on Army Cpl. Eddie Ward's leg after he stepped on a land mine. After the first wash, doctors must cut away all the tissue that is dead or dying. Pink and red are good colors. Purple and blue must be removed.

A surgical technician cleans up after Army Cpl. Eddie Ward's surgery. Ward faces multiple operations, painful rehabilitation and a long recovery. Tattooed on the back of his forearm are the words "No regrets."

Army Cpl. Eddie Ward, 19, is still sedated and on a ventilator when Army Brig. Gen. Kenneth Dahl comes to present his Purple Heart, the combat medal awarded to soldiers injured in action. Often when medals are awarded at the hospital, the recipients aren't conscious - officers prefer to give the medals before service members leave Afghanistan.

Medical personnel wait for the next patient. Casualties on stretchers will be rolled into the hospital on these rickshaws.

Petty Officer 3rd Class Carteze Leverett, a reservist from Columbus, Ala., rests in the trauma department during a down moment. Leverett is a hospital corpsman. Tours here used to last a year, but after too many caregivers returned home with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, the Navy reduced rotations to six or seven months.

Ata Mohammad looks up while in the intermediate care ward. He suffered head wounds and body trauma in a vehicle accident; he was stabilized and later released. "The day I got here, the average age in the ICU was 5," says Navy Capt. Mike McCarten, the hospital's commanding officer.

Lt. j.g. Jessica Belz, an ICU nurse, tries to comfort an Afghan patient who was injured in an IED blast. Belz lives in Chesapeake and works at Portsmouth Naval Medical Center. While few American patients spend longer than 36 hours here, Afghans often stay weeks because there is nowhere to send them on to. The best local hospital, Mirwais Hospital in Kandahar City, does what it can with what it has. But its capabilities are decades behind the worst U.S. hospitals.

At the end of Pvt. Dean Hines' surgery, doctors packed his wounds with gauze and sewed them closed loosely. They won't be permanently closed for at least a few more days; they must be washed out several more times to prevent infection.

Improvised explosives riddle their victims with so much dirt and debris that cleaning the wounds can take hours in the operating room. It's a painstaking job - and one that must be done right.